A girl, a boy and the land: A family preserves 80 acres

This is the story of Alix Blair and her memories of growing up on her family’s land.

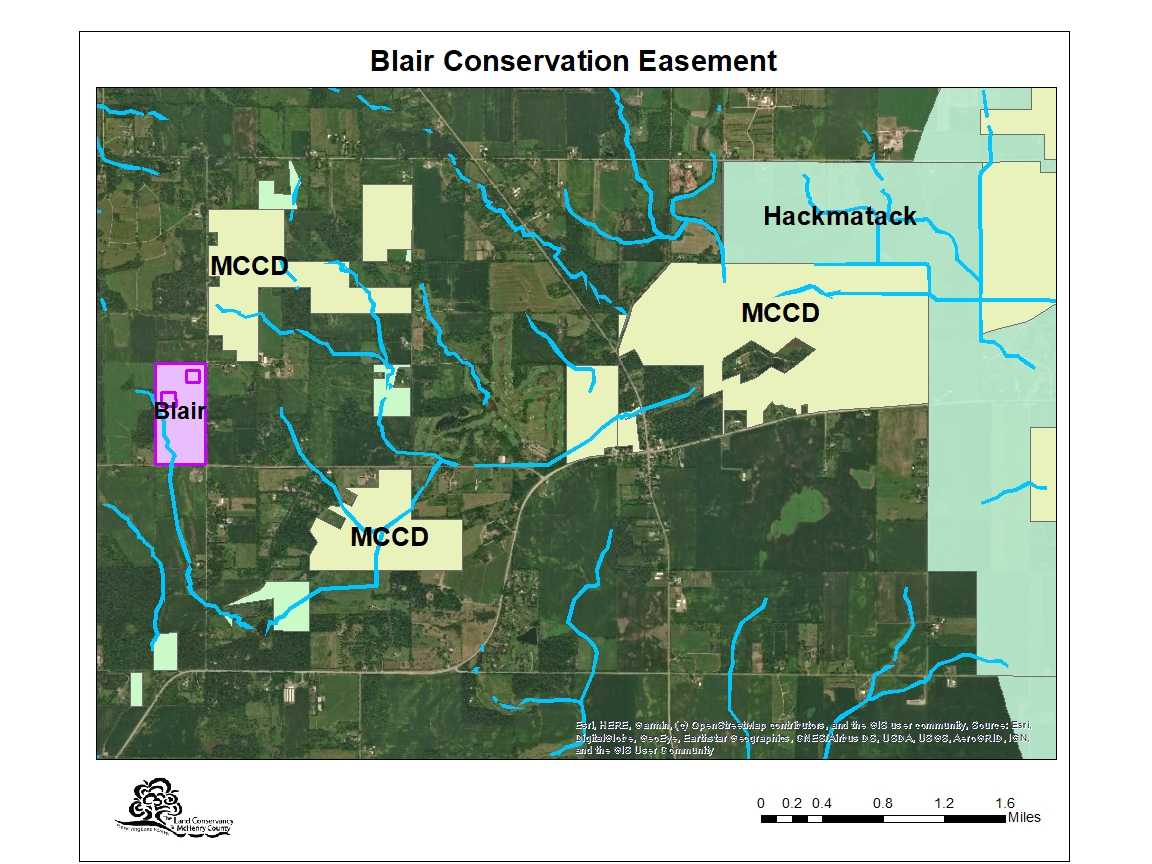

The Blair family placed a conservation easement on their land in Harvard, IL to protect it for life before transferring it to a new owner.

One of my first memories of our family’s land was running bare-legged through nettles with my brother. I was probably nine years old at the time, and my brother was six. My parents had put whistles on long, colorful lanyards around our necks and explained that if anything bad happened, to blow the whistle: we were city kids turned loose to explore. In our adventures on this day, early in the time that the land became ours to steward, we raced in shorts through a long and tall patch of nettles, and being city kids, we had no words for what had happened. We screamed and blew our whistles. When my mom found us, though my legs were aching and blistered, I was curious and fascinated. All I could say was bees had stung us all over our legs, but we never saw any bees. This was a beginning of deep reverence for the land, its plants, trees and animals.

We lived in Chicago, right in the middle of the city, a few blocks from Lake Michigan. We had a small, mostly concrete and brick backyard. Both my parents had childhoods that gave them land to roam—my mother in northern California and my father in Maine. Chicago could not meet their yearning for a connection to land. They knew they could not be happy if they did not find a way to be in nature, at the very least, on weekends.

In 1988, 80 acres of half-wild, half-cultivated land in McHenry County became ours. There was no house, and so with friends, my parents built a post-and-beam house and barn. There were no trails, so my parents bought a John Deere tractor and thoughtfully made trails between the two roads and two fence lines that marked our property. We planted a garden. We planted an orchard. We came to know the wild crab apple trees, the endangered irises, the secret springs (there are seven on the property). As kids, my brother and I helped with controlled burns, learning the importance of fire in a prairie ecosystem. Our work as a family on Saturdays and Sundays involved clipping down grapevines that choked young oak trees.

I named trees, climbed them and sang to them. I greeted them as friends. One I called “Scoliosis Joe,” a scrawny oak, thin and hunched over trying to access sunlight, with fat leaves that were far greater than his trunk. I loved him. I checked on him each weekend.

My brother and I had hide-and-seek games we played in tall grass which we called “cutting grass” because sometimes the blades gave us small nicks like paper cuts. We often spooked resting deer in the cutting grass; we felt bad to scare them, and also delighted in the surprise—that the tall grass could hold such mystery! We had a hill called “Cloud Hill” where we’d lay on our backs and call out shapes in the clouds. But first you had to walk by Turtle Creek and the tree where the groundhog bit through our dog’s foot. We loved the land with all our naming. The meadows and forest, the threshold were wild turned into field—these places held our memories and our imagination. We were a blip in time for it (30 years), but for us, those acres defined our family. During the week, we were each lost in our worlds of work and school. Then on weekends, we were the happiest I remember. We loved the nesting hawks, the pheasant and the milkweed that fed the monarchs. We gathered acorns, which felt like marvelous treasures holding the promise of giant trees.

I am now a new mother. As I write this, my eight-month-old son is sleeping upstairs. I am grateful that he was able to meet our land before we sold it. We let it go for many reasons, one being that no one in our family lives in Illinois anymore. I spent three years trying to think of a way to keep the land, until it was so obvious that the kindest thing to do was to let it go to someone new who would love it as we did. I believe that most of the goodness in who I am comes from growing up on that land.

On my last day there, knowing that most likely I will never see it again, I walked with my baby to the giant, ancient oak trees that stand by a curve in the long driveway. I watched woodpeckers jump from trunk to trunk. I told the trees how grateful I was that my son could meet them, grateful that I had grown up with them. I thanked them for making the oxygen we breathe. I thanked them for their strength and resilience in all the years they had stood there, grown from tiny acorns, watching over the human beings that come and go.

Alix Blair